Moonlight Shows a Man Struggling to Understand Himself

Moonlight asks its audience to do something that is extremely difficult to successfully pull off in a movie — something that if it is pulled off seems effortless. It asks us to understand its main character, Chiron.

Normally this isn’t such a big deal. In fact, for most movies something like this isn’t even worth pointing out. In order for a movie to work, fundamentally, we should have some sort of understanding with the main character. Plots don’t work without this. Moonlight is different. The fascinating thing about Moonlight is that there really is no plot.

Let me explain; there is a plot — technically — just not in a traditional sense. We’re not given a straightforward narrative. It plays out like the fractured memories of a man reflecting back on his life.

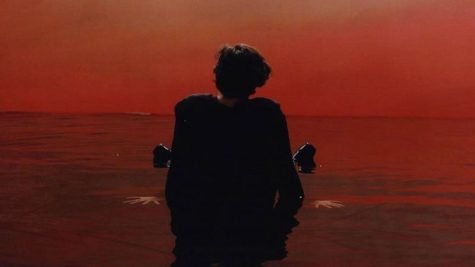

We see his life in three pieces. The first segment is called “Little”. Chiron looks to be roughly 9 or 10 years old, and our first shot of him is from behind. He’s running. Some kids from his school are chasing him to beat him up. Over time we learn this isn’t a rare occurrence. Chiron gets picked on a lot. His life isn’t great. Aside from this, he is growing up in the slums of Miami (hypnotically shot by cinematographer James Laxton), struggling with poverty, and being raised by his crack addicted mother (Naomie Harris). So then it doesn’t come as a surprise that he ends up befriending drug dealer Juan (Mahershala Ali) and his girlfriend Teresa (Janelle Monáe, oddly, of all people. She’s a good actress). They end up being a better family to him than his actual one, and Juan quickly becomes a father figure.

The second chapter, “Chiron”, picks up a few years later. Chiron appears to be about 15. Now in middle school, he’s is still a bit of an outcast and is picked on. By now it has become apparent to the world around him that he is gay, yet he is still a bit unaware. Another student, Terrel (Patrick Decile), takes a special hatred towards Chiron, becoming increasingly hostile and violent to him.

The third chapter, “Black”, finds Chiron in his mid 20’s. Never explicitly stated, we get to see how his life, and the people he’s met, have shaped him to be the man he is now.

Rarely is his life a fun one to watch. In fact, it is almost unwatchably grim. Its saving grace — and part of the reason it is so extraordinary — is how restrained writer/director Barry Jenkins is with his treatment. Maybe it’s because of his similar upbringing that allows him to see his story as more than a sob-fest. He never overbear his emotions. There is no swelling orchestra behind the sad scenes to make sure you’ll cry. There is a quiet honesty to it. Take, for example, a scene in the first chapter when Chiron goes to visit Juan. Their conversation starts out innocently enough, but quickly reveals that Chiron has other things on his mind when he asks Juan first, if he is gay, and second, if he was the one who sold his mom crack. It is undoubtedly painful to watch, but Jenkins doesn’t hammer this point home. Juan can’t look Chiron in the face when he answers him, letting us know and feel all we need to.

And as much as it is about how some people are truly born trapped, it would be a sin if I didn’t say it is also about his sexuaity. In Chiron’s case, those two things are closely related. As rough of a life that he is given, it feels like a cruel joke that he is beaten down even further just simply for his sexuality. That is the other reason Moonlight is so extraordinary. It achieves its one goal; it lets us understand him. It grants us much needed insight to a life that many do not understand.

It’s a life lived on screen, similar to how Boyhood worked. But where Boyhood caused us to look inside of us, Moonlight makes us look inside someone else. And for 110 minutes, we do.

James Mason is a writer for Temple University. When not writing for the newspaper, he can be found at home reading badly, writing badly, viewing bad...