Local psychologist discusses the pandemic, politics, and society at large

An in-depth interview with LifeGrowth Psychological Services’ owner and founder Dr. Carmen Ranalli Morrison.

Carmen Morrison, Ph.D., believes that everyone is made up of emotions, thoughts, relationships, bodies, and spiritual selves, according to LifeGrowth’s website. She goes between treating patients at LifeGrowth and running an international nonprofit called Reclaim Life.

In the aftermath of school closures and stay-at-home orders issued by Governor Wolf, many students have admitted struggles caused by the loss of the sports season and other events such as graduation, loss of social interaction, and feelings of stress and anxiety. Carmen Ranalli Morrison, Ph.D., is willing to shed some light on how the world-wide pandemic could affect children and adolescents.

Dr. Morrison, owner and clinical supervisor of LifeGrowth Psychological Services in Boyertown, earned her Ph.D. in Psychology from Fuller Theological Seminary in Pasadena, Ca., in 1994. In addition to her Ph.D. she also holds a M.A. in Theology and a M.A. in Education. When she first started out, her focus was more on childhood adolescence, but more recently she specializes in family work, marriage work, and psychological testing for children and adolescents.

“From the beginning, when I started the practice and it was just me all by myself, I think really the driving passion has been to provide the most excellent, cutting-edge psychological care in a way that’s accessible to as many people as possible,” Morrison said of LifeGrowth, which was founded in 2006 and now employs seven other specialists.

Recent trends with the results of the pandemic goes two directions, Morrison said. While receiving less patients since the state-wide shutdown, she’s also noticed people either love or can’t stand being around their family so often. Either one, she says, is a positive.

“One is parents who are just like, ‘I can’t be around my kids this much,’ and they didn’t realize that. It sounds like a negative thing, but I see it as a positive thing because it sort of spotlights things that weren’t manifested in just the bustle of everyday life, things that they can now attend to,” she said. “I’ve also had families, couples going, ‘Man, being at home together, and working together, and just having this relaxed family-paced life that when we’re both working we just don’t have… we really like this.'”

Licensed in both PA and Texas as a psychologist, Dr. Morrison has been practicing since 1995 and is affiliated with the Pennsylvania Psychological Association as well as the American Association of Christian Counselors.

When things start to open back up, the transition will be jarring. Morrison says she expects a delayed response in terms of how its affected mental health.

“I actually think it’s going to be like a mushroom at some point, probably when things start to ‘return to normal,’ but it’s not going to be normal,” she says. “Transitioning back, starting to think about how do we want to do our lives differently going forward so that we can preserve some of the things we’ve discovered that have been so positive for us relationally.”

Dr. Morrison expects minimal effects on mental health for children and adolescents.

“Always like everything is, it’s going to be mediated through the parents and the family system,” she says.

She explains that for children, if the parents are “stressed out, freaked out, anxious in the circumstances,” then the children will “have more behavioral issues or become more anxious” as a result.

“Mostly behavioral issues, because that’s how children communicate their need is by acting it out,” she says,”they don’t have language for it. They let us know that they are hurting or in trouble and need help through behaviors.”

A way to mitigate these issues is through giving the child clarity and just enough information as the child is asking for. Parents should manage their emotions, but not in front of the child, “so that when they’re interacting with the child it’s very much focused on their needs.”

“Child security comes from the relationship with their parents, so if that stays okay then they’ll be alright in terms of what’s happening around them,” Morrison says. “If there’s not security in that relationship, if the parents are frustrated with the behavior and just yelling and sending them to their rooms, then that stress in addition to then what they know or hear about in terms of what’s going on outside, can then really be difficult for a school-age child.”

Much of what psychological research has found in healthy childhood development and healthy development of relationships has been lost in American society, she says.

“We have such good science right now, such good science with all the advances in neurology in the last 15 years, knowledge we just didn’t have when i first started out,” Morrison says. “Like we know what to do to have a child be able to develop who they are in a healthy, balanced, whole way, and they’re really, really simple things. And yet, I think in American society in particular, the capacity for that just seems to be diminishing, which is just so heartbreaking to see.”

Parents, she says, who do really care about their kids, may work under assumptions of parenting that may put the child at risk for future mental health issues.

“I preach this in my travels all the time: it doesn’t take money, it doesn’t take education, it doesn’t take status or a title — anybody can do these things [to provide healthy development],” she says. “I just feel like as a society we’re becoming more arelational — meaning not really knowing what it takes to make relationships work — whether it’s in marriage, which we have right now a divorce rate that’s almost about 60% of the population, which is horrific. It keeps me in work, but I’d rather be out of work.”

Effects on adolescents are more difficult to assume, as there are more variables to consider. Despite these variables, research points that a connection with parents is the most important variable to consider.

“I mean, I’m 56 years old, I still love knowing that my mother puts me ahead of her in her life,” Morrison says. “There’s a real securing thing in knowing that there’s somebody who, no matter what happens out there, is watching out for me. That’s a really securing thing at any age.”

Other variables may include the losses, such as with graduations or proms, time with peers, and vulnerabilities.

“The general rule of thumb is that if someone was already struggling before this happened with trauma, anxiety, depression, suicidal thinking, substance abuse, then those are already vulnerabilities and then the pressure of the circumstance on top of that can cause those things to mushroom,” she says. “If I was already struggling socially, or was awkward socially, or had some social anxiety, or felt like an outcast in my social structure in my school, then this can sort of further that or can highlight it and shelter it and make kids go, ‘oh, well I don’t ever wanna go back to school because its so much easier being away from that.'”

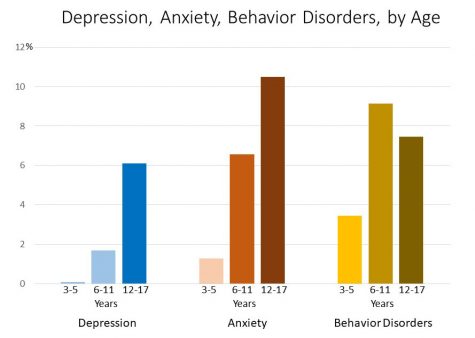

Adolescents are more frequently affected by mental health issues compared to children.

Students who have a really good social group in school are “probably managing it okay through social media,” and anyone who has a support system will most likely be okay.

“There’s a lot, we have all of those individual variables. And so that’s always something to be really mindful of,” she says.

The shut-downs make everyone a little bit more anxious, she says, but that may not necessarily turn into an anxiety disorder.

“We know from research with epidemiology, or population incidences of anxiety, is that anxiety affects depending on which study you look at. So there’s a range, between 10% to 30% of people over a lifespan. That’s not at one moment in time, it’s over the lifetime,” she says.

Based on the research, “say 15% of the incidents may be genetically loaded, or biologically loaded in some way,” she says, but the “vast majority of anxieties is environmentally mediated.”

“So the great news about that is we can change environment,” she says. “I can’t so much change genetics, but I can do a lot with environment.”

She says the most important thing for anyone is to have a connection with somebody.

“You’ll hear this through everything I say, because it truly is the one scientific finding that we have that’s cross-cultural, universally human,” Morrison says. “[Having] somebody who is accessible to me who can respond to my need, cares about me, is going to protect us from anxiety.”

The first thing she does when she’s scared, she says, is go to her husband and talk to him.

“He gives me a hug, and all of a sudden I’m not as scared or I’m not as stressed anymore,” she says.

This reaction has a lot to do with the neurochemical oxytocin, called the “bonding hormone,” or the “love hormone.”

“There’s some certain kinds of things that release oxytocin, and it has this very calming uplifting effect on us in terms of what we’re experiencing,” she says.

Risk factors lie in when a student doesn’t have a safe connection with somebody who can soothe anxiety symptoms. Having situations such as a stressful home life with no secure connection to someone creates “anxiety with no place to go and nothing that can soothe it.”

“It’s not just that the pandemic is going to cause anxiety as a condition,” she says, “but whether that turns into anxiety where we’re just thinking about it all the time, and worried about it, and feeling like my life is never going to be worth anything because of all that’s happened, and there’s that sort of preoccupation with it — then that’s becoming more in the disorder kind of camp, and so those are things that we would want to attend to.”

Signs of anxiety and depression that students and parents should look out for include looping negative thoughts, changes in sleep (too much or inability to go to or stay asleep), changes in appetite or weight (eating a lot more or a lot less than usual), fatigue, and difficulty concentrating. For depression specifically are symptoms of hopelessness, feeling alone, and feeling less worthwhile.

“With anxiety, it can also just look, especially in adolescents and children, just more like irritability, snappiness, ‘disrespect,'” Morrison says, “which I put in quote because I just see it as communication of need. A reactive, irritable anger can be symptomatic of anxiety and depression as well.”

Oxytocin is widely accepted as a “love chemical,” as it is triggered by physical interaction. Oxytocin is associated with the parts of the brain referred to as the “reward system,” making it a very calming as well as addictive reaction.

Dr. Morrison stresses that there is help for students who need it; adolescents would just have to ask their parents about insurance coverage.

“I don’t know how other people are structured, but on our website we have a form, you just type it in and then somebody gets back to them,” she says.

During the stay-at-home orders, LifeGrowth has been using Zoom predominantly, with Doxy.me as a backup. Both video conference platforms are HIPAA compliant and secure.

“I’m very fond of saying that the best time to seek help is when you feel the need for it,” Morrison says. “The reason that I say that is I find in the years I’ve been doing this that most of the time people wait to seek help until it’s really bad.”

Waiting to seek help for a possible mental health issue is like having a broken leg, she explains, and continuing to walk on that broken leg for a week, a month, or even a year. Waiting until you’re really “crippled” to seek help will require breaking the bone, putting pins in it, surgery, rehab, and an overall longer and more painful recovery time than if you had just gone to get a cast when it happened.

“Like, most people, if they’re gonna have difficulties in their marriage, they wait until somebody’s had an affair or when somebody’s threatening divorce, and things are really, really bad, and then we reach out for help,” she says, “as opposed to saying, ‘we’re really wobbling and we just can’t find our way out of that, lets just go get help before it gets bad.'”

She says that if adolescents are really struggling and are unable to shake it off, even if it’s just a short-term issue, it’s much better to address it than wait.

“It’s much easier to [heal] and much shorter to do it when it’s sort of just at that wobbly stage, before its become this huge thing that’s taking over my life,” Morrison says. “If you feel the need, if you’re struggling, that’s the time to seek help.”

There are many ways to cope with stress or anxiousness, that Dr. Morrison focuses on security, structure, and playfulness. Security — a connection with at least one other person, where “I can talk vulnerably about what I’m feeling or what I’m struggling with,” — remains number one.

Structure, or rhythm, is another significant way to help oneself.

“So when we’re at school, we have our schedule: I go to school, bell rings, it’s first period, bell rings, there’s a rhythm and a flow that I can anticipate every single day,” she says. “When that’s all of a sudden gone, and I just have to structure myself — that’s not easy for anybody. And so there’s not that same predictability, and predictability is even more important in times that are super unpredictable, which is what we’re living right now.”

Morrison advises students to “create your own schedule,” emphasizing to not make parents force you on a schedule, because “that’s just going to be miserable for everybody.”

“Do it for yourself, and do it not because you need to be ‘disciplined’ or you need to be ‘responsible,’ but do it because we all have a need for a predictable rhythm of what our day is going to look like,” she says. “So figure out what you want your day to look like, and then that’s your schedule, your structure that works for you.”

She acknowledges that parents might need some help accepting the structure.

“For example your rhythm might be: I’ll get up at 11, have my breakfast, start school work at 12, work for 2 hours, and then go on to chat with my friends on whatever medium I like to use,” she says.

She explains that adolescents have a day-night rhythm that’s different than children and adults, where the brain doesn’t go into a “sleep mode” until later at night.

“Really they would do best if they could go to bed at 11, 12 p.m. and get up at 10 in the morning,” she says, “and that the average adolescent needs about 10 hours of sleep, which nobody gets. So if you just let your body do what it wants to do, a lot of adolescents are going to be doing that, and then they’re going to have parents freaking out at them going, ‘you need to get up, you need to be doing something, you cant be sleeping all day,’ and that misunderstanding can cause some conflict.”

The last way to cope — playfulness — is important at any age.

“It’s such an important part of helping our brains regulate,” she says. “And so if I feel crazy or uncertain, or things feel real stressful, but I can take a pause and ideally sit down at a family level and play games, which I always recommend, it’s a wonderful thing to do with time stuck together in the house.”

She highlights using apps to play with adult children or friends, watching movies together, or doing fun activities like having nerf gun wars in the house can be very beneficial to relieving stress or anxiety.

LifeGrowth Psychological Services, established in 2006, resides in the Boyertown Professional Center. The insurances it accepts are as follows: Highmark, Most Blue Cross Blue Shield plans, Aetna, Independence Blue Cross, Capitol Blue Cross, Personal Choice, and Keystone.

“Just to play, and make sure we’re doing that with somebody so we have a little bit of laughter and levity in the middle of all the other kinds of craziness,” she says. “Most American families have forgotten how to do that.”

Within American society, self-diagnosing has become very trendy with information on mental illnesses readily available all over the internet. Dr. Morrison sees this as both a positive and a negative.

“I’m a huge supporter of being self-aware, self-educated, and taking responsibility for your own health mental or physical and being an advocate for yourself,” she says. “It gives you a starting point, bring that to a professional. It gives you the ability to go, ‘okay this is the way that it’s presenting, let’s look at all the different things that may be contributing to that and make sure that that’s what we’re looking at.'”

The danger in it, she says, is when people don’t seek out a mental health professional for evaluation, as the self-diagnosis may not be true. This is an issue prevalent in videos on YouTube, which analyze parents or children as “narcissistic.”

“For any single diagnosis, any one, I can give you ten different things that have brought it to that,” Morrison says. “So, our diagnoses are really just descriptions, they’re not labels, they really don’t mean anything. They’ve just been made up on the basis of research; this is what it’s looking like, these are the manifestations or the symptoms, and we put a category around that that helps us describe it, but its not really a thing in and of itself.”

It’s not like a physical illness like COVID-19, which a doctor can test for as a discrete, measurable thing. There can be many causes for any single mental health issue, so any mental health diagnosis is more of a description.

“Anxiety, for example. I can have anxiety because of food sensitivities, because of a thyroid disorder, fluctuations in blood sugar, because my parents are going through a divorce — which is different than just ‘I have anxiety,'” she says. “I think one of the things that’s professional that helps is when you have somebody who understands all those different kinds of things.”

One practice that Dr. Morrison trains everyone at LifeGrowth to do is ask about what the individual is struggling with, and then ask about what could be causing the struggle. They then rule out the options that aren’t viable and work through the ones that are; this is an expertise that is missing from self-diagnoses.

“It’s very tailored to you and your presentation and your history and your story, and you’re going to treat all of those differently,” she says.

Diagnoses can have issues even in the mental health field — in the form of over-diagnosing.

“Over-diagnosing is a huge problem, and if you go inpatient anywhere, that always happens,” she says. “Back in the late ’90s, early 2000s, I would always joke and say that I could send anybody to an inpatient facility and, this is not an exaggeration, 100% of the time they came back to me with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder.”

With incidence reports in the population not supporting that number of bipolar disorder diagnoses, she says, as well as her being the treating therapist and not seeing where that diagnosis came from, presents huge issues in the professional field.

“It was sort of like the diagnosis du jour,” she jokes. “We also have to realize that there’s more research right now coming out about how there are mind presentations, so neurological presentations of things that are related to our food and our environment with the level of toxicity.”

This research is beginning to show how even genetically loaded mental health issues, like bipolar disorder — the second most genetically linked condition after schizophrenia — are impacted greatly by environmental factors.

“One of the first things I always say to people is, ‘let’s look at what you’re eating, let’s look at your body,’ and that may not be all of it, but if it takes any chunk of a load off of what you’re dealing with — well, then, that’s really worthwhile to do,” Morrison says. “I’ve never worked with anybody with bipolar who doesn’t improve dramatically by doing some things with food, with nutrition, with helping the whole body.”

The reason there’s so many over-diagnoses, she says, might be because professionals just look at the symptoms instead of what’s causing it.

“There’s a lot of different threads that could be there,” she says. “It is a problem, because then it loses its meaning. If everybody has bipolar disorder, then it’s sort of meaningless. It doesn’t really help us distinguish, it doesn’t really help us treat, so I do get pretty bugged by the over-diagnoses especially with bipolar.”

Many people who are prescribed psychiatric medication end up taking several to try to mitigate negative effects of others.

Another issue within the field comes with too much reliance on medication.

“Medications need to be used much less than they are, truthfully,” Morrison says. “For me, medication is a valuable tool to have, but as a last resort. It’s rarely that I would be doing it right away, unless there is a safety issue or where the person is just so stuck neurologically — in their neurochemistry — that they can’t even make use of treatment.”

While she sees a legitimate role for medication, all psychiatric medications have equally negative side effects, and rarely do they solve the issue like therapy can.

“It’s like a tradeoff, and — let’s just talk about anxiety — based on research of the protocol I use with anxiety, I can tell you that 85% of people will be better from anxiety — that it’s 85% ‘curable,'” she says. “The other 15% are gonna be better enough that it’s going to be manageable. And most people who’ve struggled with anxiety go to their doctor first, not to a mental health person, that makes me crazy, because all that a doctor has is a drug that does not do anything to heal the anxiety — doesn’t fix it — it just masks it, it just diminishes it.”

With medications such as antidepressants, for example, rarely do the antidepressants take somebody out of the clinical range of symptoms, she says. It might bring the symptoms down, but they’re fully symptomatic in terms of diagnostic criteria.

“It’s not really doing what it’s sort of accepted that it does,” she says, “it doesn’t fix it, it doesn’t cure it, and most of the time it just makes it more tolerable — it doesn’t make it go away.”

Therapy, on the other hand, can effectively help people heal better than a medication can, without negative side effects.

“It’s because most people go to a doctor, who has a medical model which is ‘there’s a symptom, let’s just make the symptom go away even if that’s not the cause of the symptom, let’s just erase the symptom,'” Morrison says. “And so I would love to see people who have mental health issues go to a mental health professional first, and then if medication is indicated we’re all trained to make those referrals and to know when to do that.”

Even greater than that misstep in society are vast misconceptions about mental health due to lasting stigmas as well as pop culture and media. Though much less stigmatized today, there is still a disparity between “accepted” mental health issues and ones that are seen in a much more negative light.

“Two generations ago, going to see a psychologist would have been embarrassing, you would have never wanted anybody to know it. Now, teenagers talk to everybody like, ‘oh, you know my therapist said,'” she says. “But there is a little bit more acceptance or compassion for anxiety, depression, than for substance abuse or dependence, bipolar, even attention-deficit kinds of things, learning disabilities — I mean, kids will take a beating in school from other kids if they have difficulties with learning.”

The number one vehicle for change are the people affected by the illnesses themselves — to not “own” the illness (as in “my anxiety” or “my depression”) and to instead acknowledge that it is something that has happened to them, and not a reflection of their character.

“I’ve never known anybody who woke up and said, ‘Hey, I wanna be severely depressed today,'” she said. “It’s something that’s happened to us, so if I can be secure in that then we will be able to present to others in a way as to say ‘I don’t accept the stigma.’ People who seek psychological help are the bravest people I know, I’ve never worked with a weak person — weak people don’t come to my office, right?”

Issues such as bipolar disorder, which has a chance of being inherited of around 60 to 85 percent, are unavoidable — nobody asked for it, nobody sought it out, she explains. The ability to look at both sides of an issue, instead of falling into “cancel culture,” — the idea of completely shutting down anybody who presents an opinion or action that you disagree with — can also help people be compassionate and get rid of the stigmas.

“We are so quick to take offense that we’re incapable of giving grace to other people, and so somebody says something or does something that bothers me in some way, well then we try to shut them down which makes it impossible to ever come alongside them and help them or offer compassion or receive that for ourselves,” she explains. “I keep hoping that your generation will step up to this challenge — to begin to go, ‘you know, all behavior is communication of need.'”

Even something as simple as asking a question differently can make a difference.

Hundreds of Pennsylvania residents gathered outside of the state capitol in Harrisburg Monday, April 22 to protest shutdown measures.

“If somebody is acting in a particular way that’s bothering me, I can either go, ‘why are they doing that, I didn’t deserve that, they’re such a,’ whatever, or I can go, ‘wait a minute, what’s going on with them, something’s going on.’ Because they weren’t born like this, right, they were born as a beautiful little baby, and somehow they’re really struggling,” Morrison says.

This issue extends to politics, where recent protests against shut-down orders sprouted up all over the country. The danger of such polarized thinking, such as only listening to one side, can lead many to “confirmation bias” — seeking out facts that favor your particular opinion, or twisting facts to fit it.

“We’re all very easily influenced by these sort of mass shifts in a group mentality, a mob mentality, we can all get sucked into that and we like to think we’re immune to it but we’re not quite so much,” she says.

From the beginning, even during the 2016 primaries, Morrison was watching Drumpf, she says. He’s brought a “whole new different kind of politics into play,” she says, which some would argue is beneficial or negative.

“From a social-psychological perspective, if you have somebody who is a leader who — he doesn’t even have to espouse it, he doesn’t even have to support it, he just, like he did with the protests, sent out some tweets that were like, ‘yes, protect your freedoms.’ And for people who are already sort of teetering, now it’s sort of like social permission to let go of constraints that, as a society, you have to have. Some things need to constrain us or there’d just be living chaos,” she says.

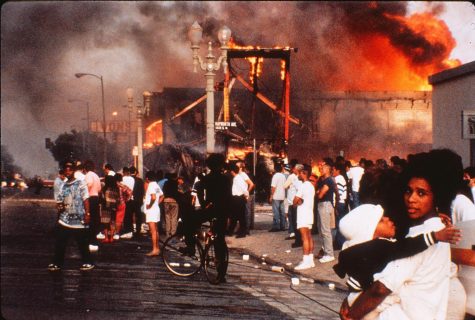

Mob mentalities like these protests have been seen before, such as in Charlottesville a few years back, as well as in the 1992 Los Angeles riots, which Dr. Morrison experienced first hand.

“I was living in the Los Angeles area when I was doing my graduate studies during Rodney King,” she says. “It was like the first police beating caught on video — now, it’s not a big deal, but not many people had cellphones then — and then African Americans just went out into the streets and were just looting their own businesses, putting things on fire, beating up anybody that was on the streets. And these were people that I know, like I knew people who were involved in that who were my friends, who would just go out and do criminal behavior. If you had asked them the week before if they were capable of doing that, they would’ve told you absolutely not.”

This type of mob mentality even goes back to Nazi Germany, according to social-psychology studies, she says.

“You had family people — loving husbands and fathers — who went out and slaughtered thousands, and went to bed at night. Like, how does that happen, how do you or me become like Hitler?” Morrison explains. “Like how do we go from here to there? We like to think of him as a madman, but most of those war criminals were just ordinary people before Hitler came and started firing up fears and insecurities and divisions. It has an impact.”

The L.A. Riots, sparked by the police beating and arrest of Rodney King as well as the acquittal of the officers involved, left many Los Angeles businesses looted and in flames. 63 deaths occurred and over 12,000 arrests made between April and May 1992.

No matter which side of aisle you find yourself in, she says, “we have to realize how much who we choose to listen to is going to affect us.”

“If we only let ourselves be influenced by one set of things, we don’t really realize how that can propel us into behaviors that we would never do otherwise,” Morrison says. “If we only let ourselves hear one thing, we’re not gonna be doing critical thinking. And if we cant hear something that opposes that, and be able to discern, ‘okay, what’s a value here, I agree with that, I don’t agree with this,’ then we’re going to be just as liable to get caught up in mob mentality as any other human being; we’re just super susceptible that way.”

Dr. Morrison currently travels a lot, having co-founded a nonprofit called Reclaim Life, whose goal is to work internationally to bring mental health initiatives that can be grass-roots led and self-replicating to urban slum communities in the developing world, she explains. Her time in town is disrupted, and she has a lot of fun focusing on the nonprofit. Her practice, LifeGrowth, can be reached for mental health consultation, as well as family and marriage counseling and many other programs, through the website: https://www.life-growth.net/. The practice is located in the Boyertown Professional Center at 137 Montgomery Avenue in Suite 105.

Jocelyn is a graduate of BASH. She served three years in the CUB and she previously wrote for the East Observer. She was in many clubs, such as SADD, Stage...